On a recent, brief but brilliant, trip to the Arisaig / Morar area, I realised I have been holidaying in the Scottish Highlands for coming up (in 2023) for fifty years now.

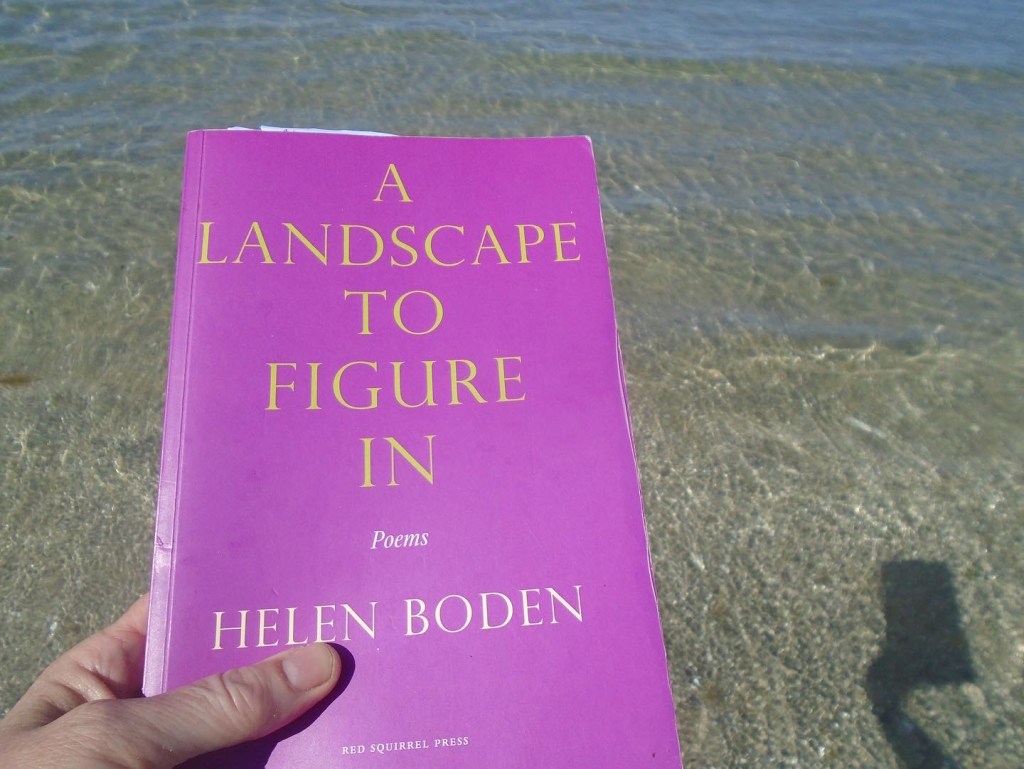

My debut poetry collection A Landscape To Figure In was published by Red Squirrel Press last November. It’s about place and identity, and one of the soft-promo things I’ve been enjoying doing is taking it to places that feature in it, and taking photos in situ – in the wild – in different weathers and seasons. This may entertain friends more than it sells copies, but it’s been an important part of post-production for me – getting to read out loud, back to, and in front of, some places that inspired it and that figure in it. (Lest that sound narcissistic, this is something I have long done with words from others’ books. I think it can be a beautiful thing – to let the words carry over the air of hills and beaches, fields and moors.)

I’m a (very) late adopter of most things tech. I still don’t have a smartphone. The previous time I was in this area, midsummer 2007, I didn’t even have a digital camera. My mum was undergoing chemotherapy in Yorkshire, and would take her last breaths three months later, as an equinox sun set, over the Pennines beyond her bedroom window; through my train carriage window over Tinto Hill, and over the islands famous for sunsets that I first visited in the 70s with her and my dad. I have to live with the fact that I’d been in Edinburgh, sorting out things in my flat and organising work, and didn’t make it back in time to see her alive again – but it was a comfort, even at the time, to think of her passing against (or into?) this wider backdrop, and in this wider diurnal and seasonal context.

On the Small Isles back in June of that year it could be a challenge to find places with a strong enough (simple)phone signal to keep in touch, but I remember calling her – all well – from the top of the Sgurr of Eigg. Now on holiday in this ‘thin place’ again, memories of previous visits, and details dormant in the interim, exerted a greater pull than that of devices and social media. I logged on occasionally, though, and was moved to read – at this time, from this place – poet Wendy Pratt’s FB posts about her father’s hospital admission and death, and then her beautiful blog tribute to him.

My first encounter with the Road to the Isles was actually taken in reverse – the road from the Isles – on the way home from a family holiday on Skye just after I left primary school. Loading the Armadale-Mallaig car ferry involved a labour-intensive, time-consuming turntable mechanism – though the service may still have been more efficient than that the islands are (not) receiving this summer – with an ageing, breakdown-prone fleet, and crews stretched too thinly. As an 11-year-old already attached to the islands, I clocked the Morar beaches as something to save for another time.

I was a student when I did return, for a summer stay at Garramore Youth Hostel, between Morar and Arisaig, close to the beach that starred in Local Hero (1983); and a for lovely Easter-time break: snow on the Cuillins of Rhum and Skye, and a long, cold and beautiful day at sea on the Calmac ferry’s round to each of the Small Isles.

This summer I was a co-driver for the first time, having returned to driving a few years ago after a very long gap. I take regular work or leisure trips to the Borders, and Dumfries and Galloway, and have been to Northumberland, the North Pennines and Yorkshire, but the unavoidable motorways around the Central Belt had so far prevented me from venturing to the North and West I love. The pandemic put paid to imminent plans to tackle this, and now for the first time I drove my own car up the Black Mount from Tyndrum, skirted Rannoch Moor, onto Glencoe and out to the coast at Ballachulish, beside Loch Linnhe, and then along the Road to the Isles. It’s – too – many years since I’ve taken that road at all, as I’ve been more likely to head up to Inverness and across to the west, or take the train, which follows a differently spectacular route over Rannoch Moor. (For sure I know about the increasing problems of motor transport in the Highlands, and car use generally, and this deserves a dedicated post later.) Yes, I found old Runrig CDs to play. It was all more powerful and evocative than I expected.

I’ve been looking out the photos from the earlier trips, still in the packets in which they returned from the developers, though never sorted into any searchable order. I can’t find my pictures from the earliest trip, captured on a Kodac Instamatic – though I still have the camera. I have some photographic record of the hosteling years, from a Canon ?Sureshot autofocus I no longer possess; and an APS (Advanced Photo System, which took panoramic photos), and an SLR, which I still have, but do not or can no longer use – as if preserving them as artefacts to accompany the uncatalogued archive they produced. I didn’t go digital until the end of the first decade of this century, when I wanted to take lots of pictures of the environs of my childhood home before selling up and moving everything I wanted to keep from it, including some earlier photographic hardware, to Scotland.

My maternal grandma (Sarah Ellen – ‘Nellie’ – Booth, 1895-1987), always used to say ‘where are the people?’ when I showed her my holiday snaps. I do have plenty people-photos from a few years later, and it is both enjoyable and poignant to look through them now, at twenty-somethings larking around in wellies or by misty summit cairns. Heavens know when I last looked at them properly, but I’d be closer to that age than to my current 57, and certainly more lithe and fearless over rocky promontories.

My closest IRL friends nowadays, apart from the poetry-reading ones, tend not to be big fans of social media or tagging. I respect their wish not to be co-opted to market my book photographically or make my travels look more sociable. I’ve remained firm friends with a few fellow-travellers from earlier decades, have lost contact with some, and re-connected with others through the Socials; so it goes.

I didn’t spend all weekend lingering over memories. Camusdarach Beach invited swimming, and close attention to crabs and starfish in the shallows. I started thinking about the changes in Highland holidaying over the past half-century, too. There’s the increasing traffic that the infrastructure can’t support, and to which I was contributing, of course. The local authority seems to be making workable medium-term solutions about facilities, after what I was not surprised to hear were serious problems with parking and dirty camping last summer. Artisan foods and other goods are now widely available in shops, cafes and hotels, showcasing fantastic produce /products that help to support a sustainable life for locals; to augment the visitor experience or compensate for bad weather. Special shout-out this time to: the Arisaig Shellfish Shack, Sunset Thai Food Morar, Isle of Skye Sea Salt Company, and Arisaig Bread Shed.

Back home, I watched The Prince of Muck (2021), a documentary film about Lawrence MacEwen, laird of the smallest of the four Small Isles until his death in May 2022. In 2007 I’d stayed on both Muck and neighbouring Eigg. The contrast, or complement, between the hospitality of the benign-governed-with-consent island, and the vibrancy of one which had been in community ownership for a decade, was key to my experience – though the occasional visitor of course lacks a fully nuanced, informed understanding of a locality. Certainly the culture of both islands helped provide respite from life with a terminally ill parent.

The Scottish islands unsurprisingly became a necessary backdrop to my own grief. I spent the first anniversary of my mum’s death on Arran, location of more family holidays than anywhere else (with the possible exception of Scarborough). Places where the dominant soundscape was waves, wind, birds, and not urban traffic, gradually walked me into acceptance of a new phase in my life. I wrote the poems that would be collected into A Landscape To Figure In, grounded in the Pennines where I grew up and the Pentlands where I stay, but reaching out to, and back from, places including the US / Canada border, Italy, Zimbabwe. Domestic and theatre interiors also feature, plus several hybrid or fictive locations. And there are real – with real 21stC problems – Greek and Scottish islands and coasts. None of the poems specifically reference the Morar/ Arisaig area, and ‘landscapes’ outnumber ‘seascapes’ (though the collection plays on the terminology of both) – but this one is is after a delectable set of ink and egg tempura paintings by Emily Learmont, themselves after a voyage in the Sound of Sleat, between Skye and the peninsulas of Knoydart and Morar:

Some Seascapes

After Emily Learmont

(i) Graphic

an inkblot cloud pursues the boats

like a speech bubble

flurries of vowels morphemes ideas

on a punctuation-flecked sea

swirls whorls

of inverted commas

conversation billows

between the fleet

a thought detaches memory sprays

a wake for the clearances

will they consolidate

into a skerry of memory?

night nautical twilight civil twilight day

calm storm calm storm calm

plot the sound

I saw three. . .

(ii) Isthmus

Skeletal-chalked -

fine lines of rigging

fresh-vein the moon

(ii) Clearance

Ship parts the coasts

of Knoydart Sleat

like a centrifugal force

funnels thought

when the storm has passed

through the vessel

is that a second ship

or fata morgana

the soul of the boat

or its counterpart

inverted on the horizon

beyond the end of the sound

is the ship or weather

fugitive -

one vessel the other’s unconscious or ours

ship drops anchor in the sound

sets a lantern

a thousand onshore lights

glow back as the darkest hour departs

departs for Carolina

leaves a filigree wake

a waning moon

a morning sun like marbled paper

From A Landscape To Figure In (Red Squirrel Press, 2021)

Mapping South Side Writers. Photograph by Olga Wojtas.

Mapping South Side Writers. Photograph by Olga Wojtas.

I accidentally attended a workshop at the very excellent

I accidentally attended a workshop at the very excellent