WINTER: HUSH ON THE MAINS

A year ago I wrote a poem for Scottish PEN’s anthology to mark the 700th anniversary of the Declaration of Arbroath. Titled ‘A Declaration of Hush’, it starts, and ends, on the bridge over the Braid Burn at Colinton Mains, in the lull between Christmas and New Year – a week when I love to stay home, go for walks, do less, gather strength for the rest of winter. More polemical that what I usually write, it is a plea for quiet (and sometimes an angry or comic one, rather than being quiet itself): for listening, for toning down ‘unnecessary racket and clamour and din’ until ‘we can start to hear again’ other species and life-forms, nuance and diversity, and ‘our own hearts beat, breath and footfall’. It is also a love song to where I live, and can be read here.

I never imagined when I wrote this that the turn-of-year quiet that I find so nourishing would persist throughout much of 2020. I was not always coping well with the way the world was pre-pandemic, particularly when in crowds or on public transport. Maybe I am neurodivergent – I certainly identify and empathise with people who are; maybe this is something I will go on to investigate, but it is not the main point of this post.

SPRING: DISTANCING

I chose to move out from Edinburgh to the edge of the Pentland Hills ten years ago, not exactly predicting being locked down during a pandemic, but thinking carefully about where I wanted to be – to spend Christmases, to return to from work and other trips, to write and exercise, to welcome friends.

Thanks to a commission from Pentlands Book Festival, I have written elsewhere about my experience of lockdown locality, and how, despite fear of the virus and collateral stresses including worry about money, I was fortunate to be literally and figuratively in a ‘good place’ when we were required to Stay Home.

After a silent start, I wrote a lot. My skin, often barometer of my wider health, was in good condition – no doubt due also to lower pollution levels.

In easy walking and cycling distance from hills quietened in the absence of many other leisure users, I consider myself privileged to have witnessed the passage of a spring when the song of skylarks was louder than the noise of traffic on the city bypass. I was also, of course, relatively privileged in other ways during a pandemic that has exposed and exacerbated inequalities. I have a garden. I did have work, and lost less income than many freelance artists.

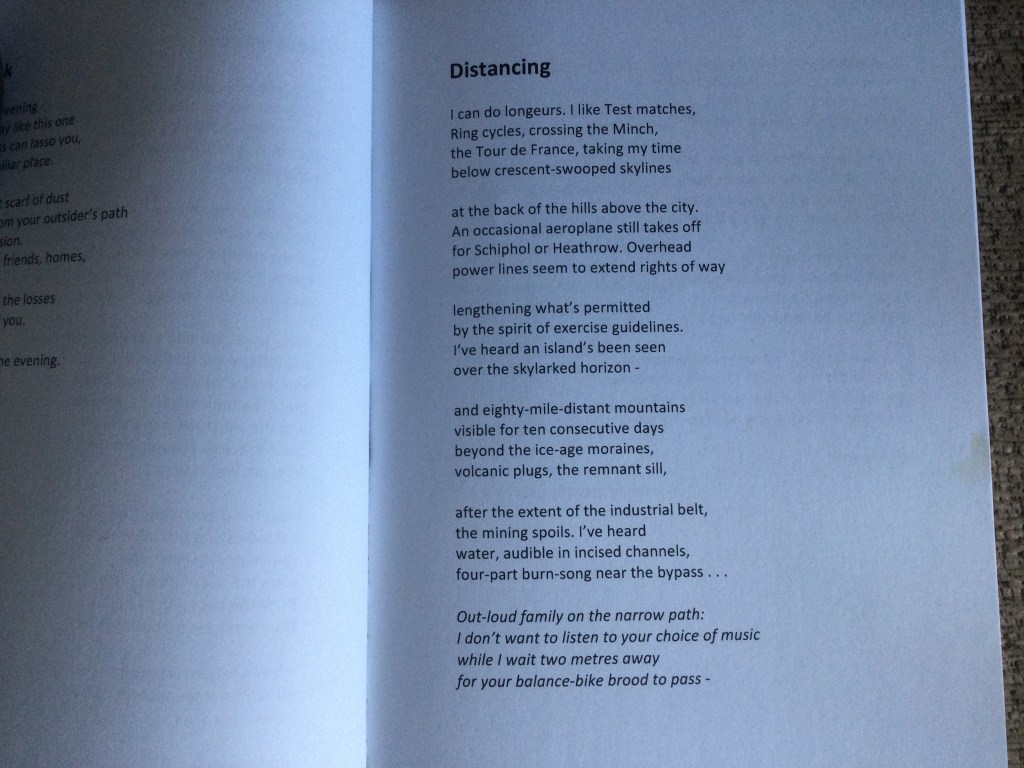

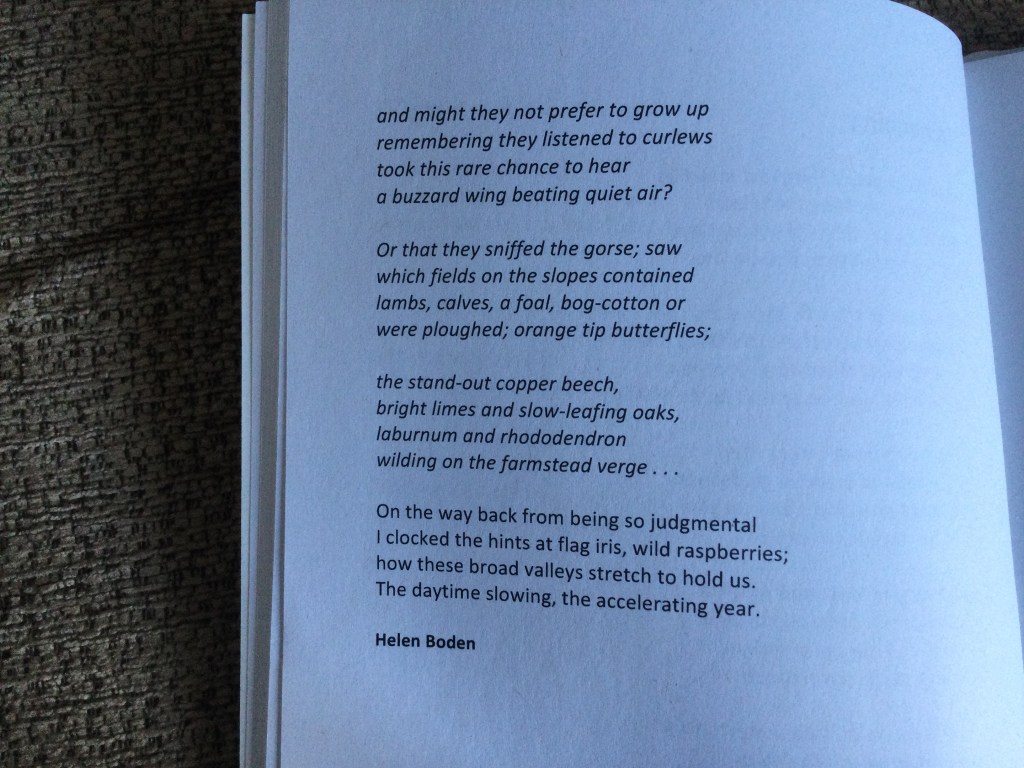

I wrote a poem for Beyond the Storm, an anthology published to raise money for NHS charities:

SUMMER: CRESCENDO

After the lockdown ‘anthropause’, the hills got noisier again and quickly became louder than they’d been before. With travel restrictions still in operation and many other leisure activities still closed, the Pentlands, like other rural areas close to urban centres, became unsustainably but unsurprisingly busy. The virus had impacted on everyone’s wellbeing, whether or not affected directly by Covid. Outdoor, green and wild places are as beneficial for mental health as for physical fitness, and there is a range of hills starting within a five-mile radius of a capital city centre.

One side-effect of the pandemic has been territoriality – again unsurprising, with movement circumscribed in a way many had never experienced before.

A post-lockdown trope emerged, and played on repeat, on the local hill users’ Facebook group: that upland and wilder areas, which are / should be for all, were welcome-policed, not by hostile landlords, but by an old guard who considered themselves to be more worthy of them and were hostile to the influx. An ongoing online debate about access, parking, littering and more crescendoed into testosterone-fuelled rage and condescending judgementalism. There was a fair cacophony on the moral high ground.

Glad that people were able to find solace and release in the hills, at the same time I was often dismayed, and at times, shocked – for example when seeing long strands of cars parked along the verges of the lanes that lead towards the hills, their drivers disregarding advice from the Ranger service, and outdoor authorities across the country, to have alternative plans in case their carpark of choice was full. It usually was after 10am, even on weekdays and in bad weather. These vehicles blocked access for farm traffic and emergency services – fire risk was now high after a long dry spell – and later, after a long wet spell, caused drainage problems.

I was most dismayed and shocked to hear music played out loud.

For every person who needs slow and quiet there is a counterpart who wants speed and noise, and this may not have been the best time to point out the latter’s unhelpful connection with adrenalin and antagonism to relaxation – we each cope in our own way; understandably many find being alone with their own thoughts just too difficult and need constant external distraction and stimulus. One of these does, however, have a disproportionate impact on the other; the effect of the quiet on the loud is negligible.

Disclosure: I’ll admit to some nimbyism existing alongside a more altruistic concern for people who live and work in the hills and for other species here; to some difficulty in compromising over the shared space. Simultaneous and contradictory truths are possible.

AUTUMN: THE HARLAW HOWLER

One Sunday I met Out-Loud Family, or another iteration of them, again. I chose, unwisely, to return from a country cycle via a popular reservoir route. A family was blocking the – very wide – track from the carpark to the water. But they had young kids, who can be difficult to organise; I swerved past and smiled at the older boy, struggling to manoeuvre his bike. Then I heard music coming from a tinny speaker on the back of the woman’s bike, glared, and rode on. The group caught up with me shortly afterwards at a bottleneck by a gate. We hung around waiting to get through, accompanied by their music, and I eventually said to the woman something along the lines of ‘can you tell me why you feel the need to play music out loud?’

Because my washing machine and car and computer and tooth were broken and my neighbour was being noisy and I’d gone out for a quiet day and made the wrong choice about the route home, my tone was quite possibly accusatory or judgy, when in fact I was just trying to ascertain their motivation and establish a civil discussion. I know that ranting at someone will not encourage them to examine their behaviour or its impact on others.

The woman replied – this was the only thing she said – ’because it’s what we like to do.’

Her husband weighed in, saying (several times, with increasing volume and aggression): ‘It’s a free country. If you have an opinion just keep it to yourself’. They rode on and left the gate open and I’m afraid I yelled after them.

I cycled homewards, but they’d invaded my headspace. How dare he . . . but, they could’ve had as crap a week as me and I may have just made it all worse for them. . .

That did not, in my opinion, make it ok for them to noise-pollute, but still. Patience, tolerance, understanding, compassion. Do unto others, etcetera. Let it go.

After tea, a bath, and food I logged onto Facebook. At the top of my news feed was this:

‘Anyone had any experience of the Harlaw Howler. Took the wife and kids . . . . We have a speaker and like to cycle listening to music. . .Anyway this older woman though it was in her right to question why we need to listen to music . . . we had to endure the dirty looks and comments . . . First time in hundreds of miles with music playing dance or chart and [n]ever been insulted or questioned. This person actually thought they could say I can’t listen to music lol’

I watched ninety-plus comments drifting in during the evening, pro and con. There were 58 Likes for someone who commented ‘I actually think it’s anti social to ride or walk in the hills playing audible music. I’d prefer you kept it to yourself.’ Three comments, quickly deleted (I reported one of them to the site admins, and another woman noted she’d reported the others), were abusive and misogynist. A couple of comments encouraged seeing the situation more from the woman’s point of view, and speculated about her mental health, though not a single one mentioned neurodiversity or noise sensitivity. In a referendum I think the Quiet side would have won, but only very marginally.

The man / husband went on to claim that I’d been scaring another family. In the moment of being confronted by him I filtered out everyone else; I hope I didn’t scare anyone, but my recollection remains that he was the one shouting – although It’s hard not to raise your voice when social distancing. I had to brace myself not to react, and alas, on finding they’d also left the gate open – the congestion had now eased, so it needed to be closed – yelled after them.

I’m not going to go further into cyber-abuse and trolling – aurally silent, but capable of creating a cacophony from which its victim cannot escape – here, except to note the un-nuanced din of online disagreement that has been a collateral effect of Covid-19 restrictions across many social media platforms and interest groups. As far as name-calling goes, I’ve heard worse, and was actually quite tempted to claim the ‘Harlaw Howler’ moniker. I was lucky to remain unidentified in the evening’s FB entertainment – no one had taken a photo. Harder to accept was the man’s belief that I had no right to challenge his behaviour, his choice to play music out loud; that he had absolutely no concept of this being unacceptable, or that others would find it intrusive or distasteful – or inappropriate in a place where people come for peace and quiet and to listen to birdsong.

In claiming ‘This person actually thought they could say I can’t listen to music lol’ he accused me (or the ‘Harlaw Howler’) of showing an unacceptable sense of entitlement, whilst failing toconsider his own family’s entitled behaviour.

WINTER AGAIN: THE USER-FRIENDLY HILLS

Lockdown #Two hasn’t silenced local traffic like #One did, but snowfalls have quietened the land again several times so far in 2021, now bringing with it new hill dilemmas, including avalanche risk. It has also produced perfect conditions for skiers and snowboarders. Unable to travel to resorts, they have, often unwittingly, posed a threat to ewes, who are pregnant, as they were at the start of the first lockdown, by scaring them away from their heft (where they know how to find food under the snow). Along with wildlife they have been forced into gullies with deep drifts and fewer feeding opportunities. Sheep have been attacked in larger numbers than usual, too, by dogs allowed to run off the leash, owners not heeding notices explaining the law about pets around livestock. More information and guidelines about responsible conduct in the hills can be found here.

I walk in the hills with friends and visitors, especially over the Christmas holidays, but most of the time I go alone. I take work there when it’s still enough to sit and do some; I pace out plans for writing workshops and ideas for my own writing. I listen. I’m quiet but not silent: one of the things I love most about hillwalking is the tradition of exchanging a greeting with anyone else you meet. I think something that has caused and escalated the Covid-era conflict is that newer hill-users don’t necessarily know about this – why would they if they have been accustomed to not acknowledging other people in the street throughout their lifetime, to telling their children not to speak to strangers, to – for a variety of valid reasons – keeping their heads down. But some are so preoccupied in their family groups, or on their phones (or, worse, playing music out loud), that I wonder why they actually bother to come to the hills and make them busier for everyone – in some places at weekends it’s actually quite hard to practice social distancing. Their sound travels far, too, when it isn’t windy, and that has been surprisingly often this winter. Some others are clearly only there for their anthropocentric adrenalin-sport and care nothing for the history or culture of the land, for those who live and work there, or for other species. I know plenty runners and mountain bikers and open-water swimmers who absolutely do not fit into this category, whose mode of travel is a means of deeply engaging with the place – and I am sure this is also true of many winter-sportspeople – but I also regularly see ‘hill-users’ who abuse the privilege of being there, oblivious to, and endangering, the hills’ natural and social ecologies.

Of course, one can never know what another person is enduring, why seeking out the hills may be a necessary outlet for them, but one especially cannot know this if they do not even make eye contact. There may have been days when I’ve been too upset or angry to speak to people in the street, but even when I cannot smile, I say hello to anyone I meet in the hills and the countryside. This very act can be instrumental in creating a shift of sensibility from distress to ease. I have a natural empathy with people in whom an ancient code of hill civility is as ingrained as the cross-hill drove routes on which they otherwise make low impact, and find their unease at the intrusion more understandable than the accusations that they are simply unwelcoming.

POSTSCRIPT

Nan Shepherd’s study of the Cairngorms, The Living Mountain, was written in the 1940s and first published in the 70s. Her advocacy of ‘total mountain’, comprising all its elements, life-forms, weather and seasons; for circumambulation over summit-fever, has rightly become a classic and a manual for non-intrusive being in upland areas. It is a model for how to understand, recognise and witness place; to marvel and to mourn as appropriate. Through 2020-21 it has been easier, then harder, than ever before, to find in the Pentlands the kind of full-sensory joy she recounts, when place and mind intermingle until both are altered and ‘one walks the flesh transparent . . . out of the body and into the mountain’ (p.106).

I’ll give the last word to Shepherd. ‘Silence is not a mere negation of sound. It is like a new element.’